Research Thesis

Singapore's Next Creative Future

A qualitative investigation into the impressions and potential impacts of generative artificial intelligence by local creative industry veterans through a series of moderated interviews.

This cover image was generated using ChatGPT Plus and only serves decorative purposes for this thesis.

20 February 2024

Note: Citations, references and appendices have been removed for this web page to improve readability. To view the full paper, refer to this pdf version instead.

abstract

Generative AI (GAI) tools has been a trending topic since the middle of 2022 with the public release of MidJourney and DALL-E 2. It was further amplified by the release of ChatGPT, which in turn spurred many organisations like Microsoft and Google to join the rush to release new A.I. tools like Google’s Gemini and Microsoft’s BingChat. Historically, AI development has always occurred in cycles. And in this cycle, due to the above-mentioned advancements in GAI, there is a trend towards the development of GAI tools for two broad use cases. These use cases surround work that is within the creative domain, or work that is routine in nature that can be easily automated or augmented. This then begs the question, how would the commercial creative industry be affected by the introduction of such technologies? Especially so in the local context of Singapore where creativity-related research can tend be to limited. As such, this research study seeks to answer those questions through a series of interviews with subject experts and industry veterans

Introduction

Background

“Today, rapid advancements in AI capabilities to create literary, dramatic, musical and artistic works continue to redefine the human role in the creative process. Most of these works generated by computers rely heavily on the underlying algorithm and creative input of the programmers; the computers are arguably akin to paintbrushes or chisels – they are tools used in the creation of the artworks.”

- Professor David Tan, Centre for Technology, Robotics, Artificial Intelligence and the Law, National University of Singapore.

Long has been the pursuit of delegating one’s work to a machine, where as Marx believed, in its ideal form, would lead society towards a utopia, defined by an abundance of leisure, unchained from the necessity of labour. As of writing, this pursuit has moved from automating the production line, to now presenting society with Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Generative Artificial Intelligence (GAI).

One of the earliest recorded ideas of AI made its appearance in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, a children’s novel written by L. Frank Baum. Published in 1900, the tale showcased the concept of the Tin Man, a humanoid robot with intelligence comparable to the humans in the story. Several decades later, concepts of artificial intelligence would be brought about by Alan Turing in 1950, who posed the question “Can Machines Think?”, introducing the Turing test to the world. This would come to inspire John McCarthy to officially coin the term Artificial Intelligence six years later. What followed would be cycles of great strides in the technology, accompanied by years of AI Winters. As of writing, AI has once again gained virality as a topic of discussion and media coverage, this time surrounding the creative industries. For the context of this paper, the creative industry is defined as commercial and professional creative disciplines that contains advertising, branding, videography and photography, multimedia design such as graphic and editorial design, video and photo production, and digital product design.

The current virality of AI in the creative industries can be attributed to several developments. First, the invention of diffusion models, an alternative to the older generative adversarial networks (GANs). Unlike their predecessors, these GAI models did not simply reproduce content from their training data, but could now also generate what could be considered original content. This superiority of the diffusion model was also highlighted by an investigation by OpenAI researchers in 2021, noting its accessibility and cheaper operational costs which compromised little on the quality of generated content. When paired with the intuitive interfaces provided by the likes of popular contemporary GAI products like Stable Diffusion’s Dream Studio, MidJourney, and OpenAI’s ChatGPT and DALL-E, the barriers of entry for creative professionals are now significantly lowered, where previously a considerable depth of technological expertise was required to engage with the technology.

This reduced barrier of entry to GAI for creative use cases has however, also introduced an array of ethical considerations, ranging from the prevailing fear of mass unemployment to the potential for misuse of the technology by “bad” actors. Additionally, with the rapid evolution of GAI in just 2023 alone, it is uncertain as to how the introduction of GAI will impact the future design practices of the commercial creative industry in the long term. This is more so the case for countries like Singapore where design research tend to be scarce.

What this research proposes is hence to investigate and evaluate the impact of these tools on the local creative industry. Specifically, this research seeks to discover the perceptions of the creative workers in the context of Singapore, their impressions towards these tools, and using these findings to inform a speculative discussion on the near future of Singapore’s creative industry.

Literature Review

In alignment with the three considerations mentioned above, the core themes of this research will be split into three pillars. First, it delves into the history of creative technologies in relation to capitalism and profit maximisation. Second, it investigates common ethical issues that surround generative AI and the creative workforce including data bias, and potential misappropriation of the tools. Finally, it surveys the contemporary creative industry landscape in light of the emergence of generative AI to speculate the near future of the creative industry.

The Contemporary and (potential) Future Creative Industry

As noted by both prominent cultural and media theorist Walter Benjamin in his essay on the Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, and Philip Hayward in his book Culture, Technology and Creativity in the late twentieth century, the emergence of new technologies in the creative industry is far from a new phenomenon. Using the invention of the camera and its impact on the visual communications industry as an example, Benjamin believed that each invention introduced into the creative industry would also introduce a shift in the level of required skill. This in turn would gradually free up the creative from the amount of manual input and labour from the preceding technology. Thus, redirecting their focus towards developing better concepts and depth in their creations instead. This sentiment is upheld to this day, with both creatives and organisations globally like IBM and the World Economic Forum advocating for GAI as just a means of augmenting creativity rather than complete automation.

For the most part, the phenomenon of new technology emerging is usually a welcome change, particularly by creatives who seek to experiment and potentially integrate these emerging technologies into their processes in order to better their craft. And just as the emergence of the camera had disrupted the field of painting, GAI, with its above mentioned capabilities to create content almost entirely from scratch, is beginning to disrupt the creative industries. The benefits of integrating GAI into one’s creative workflow was demonstrated abundantly in a series of qualitative interviews conducted by journalist Andrew Deck from media outlet RestOfWorld. The overarching theme across the findings was that with GAI, these creatives are now capable of increasing their rate of production significantly. What originally took one interviewed copywriter “227 minutes” for a written blog post, now took only “20 minutes” with GAI, while another interviewed illustrator had been able to reproduce a similar illustration in a third of the time they took for the original (Deck et al.). This increased productivity and capabilities provided by AI tools have also been similarly investigated by academics, where it has been thoroughly demonstrated that GAI technologies are already capable of producing creative work to a calibre similar to that of the average creative professional in specific scenarios such as writing and poetry.

Locally, organisations in Singapore have long begun to explore the possibilities of integrating AI into their processes. However, many of these occur outside of the creative industries. In their book, Working with AI, Davenport and Miller highlighted several international and local companies such as DBS Bank, Shopee and Singapore’s own Land and Transport Authority that already have some form of AI incorporated into their workflow. These integrations come typically in the form of algorithms that simplify workflows or reduce manual labour, allowing them to reap similar benefits as mentioned above with the freelancers interviewed by RestOfWorld. The benefits are typically akin to some form of cost saving or increase in efficiency. One prominent example is the AI-assisted banking surveillance system used by DBS which automates several hours of investigating a banking alert by analysts.

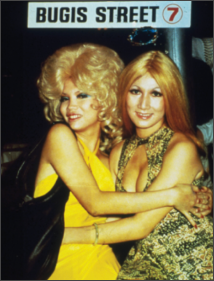

Images from Aik Beng Chia’s “Return to Bugis Street” project.

Where GAI does appear to have gained increased adoption however, is amongst artists who have begun experimenting with the tools, seeking to push their art forms. A notable example is Aik Beng Chia, one of Singapore’s most prolific street photographers, known for his works documenting cultural activities in Singapore and across South East Asia. Since its rise to popularity in the third quarter of 2022, Chia has been experimenting with the GAI tool, MidJourney, to bring some of his project concepts to life. These concepts would be difficult and costly to execute if not for the nature of GAI. One notable example is Chia’s GAI project, Return to Bugis Street, a fictitious “photo documentary” of life along Singapore’s Bugis Street in the 1970s. Through the use of MidJourney, Chia was able to recreate scenes from his childhood where he had regularly visited in the 1970s. When comparing these generated images to real documentary images of the same location during the same time, Chia’s work acts more as a reconstructed pastiche of Singapore’s history. Despite their similarities to the actual documentary images, the generations are staged to further support his narrative, which Chia had previously disclaimed was indeed the intention of his project.

Images of the actual Bugis Street in the 1970s from Singapore’s National Archives

However, GAI tools and datasets have repeatedly demonstrated that due to the nature of the initial collection of data–i.e. That they were mostly scraped from any available public domain, are indeed highly biassed and whatever that is generated is simply a reflection of that data, containing mostly cultural and historical normalities. As Chia's project blurs the line between reality and artistry, it underscores the broader concerns surrounding AI tools like MidJourney, where the generation of content raises critical questions about data bias and representation, with such biases also having the potential to introduce a level of homogeneity and sameness in the creative work produced.

Data Ethics and Representation of Data in Generative AI

As mentioned above, GAI has been in development for several decades. During which, artists and researchers have attempted to expose these biases and consequences of said biases in hopes that those working on and with the technology would make sure to take these factors into consideration. However, most of these attempts come in the form of experimentation and written literature in relation to the use of AI outside of the creative industries. While there are similarities across the industries pertaining to the potential harms and biases from AI tools and datasets, few have attempted to make this knowledge accessible outside of the realm of academia. One such attempt was Learning to See, an installation by artist and GAI researcher, Memo Akten.

Images of Memo Akten’s “Learning To See”

In this installation, Akten utilises cameras to analyse objects that are put in front of them, and generate an image based on what the GAI thinks they are. However, as the AI has no prior knowledge of these images, it ends up simply creating generations based on what it assumes the input means–which in this case, were images of space and nebulas. What differentiates this attempt from many others, is providing the general public with a tangible outcome and opportunity to witness the issue without requiring significant understanding of the technology. However, regardless of tangibility, one overarching theme has emerged across the reviewed literature regarding GAI’s data concerns. That is, unless there is human intervention, AI tools are simply programs built to fulfil a task, and as such, are likely to ignore what humans may normally be able to consider such as cultural normalities, using only what the program feels it needs to complete the task, even if it encroaches on unethical practices such as utilising inaccurate stereotypes in its content generation.

This theme has been the driving force for numerous AI companies like OpenAI to be more aggressive in their content moderation, disallowing the use of their GAI tools for numerous prohibited types of generated content which includes the generation of explicit and violent content. It has also inspired several governments such as the governments of the United States and the European Union to begin lobbying for regulations and setting guardrails in place to reduce the misuse of the technology.

As of writing, one of the latest of such developments is the G7 conference that took place at the end of October 2023 which set a list of guidelines for companies using AI technologies. Additionally, the United States Government has also signed an executive order of a similar calibre. While most of these guardrails once again exclude the bulk of the creative industries, there were several pointers that do extend to target some of the GAI data issues relating to the creative industries. These included a call to “evaluate AI systems for IP law violations”. At its core, the guardrails sought to encourage the protection of human interests which extended to reducing discrimination and bias in AI technologies. These guardrails in theory would certainly benefit the creative industries as it would come to ensure that respective creative legal rights as respected, and improve the diversity of generations across the board.

However, as multiple critics of these policies have pointed out, these policies are highly restrictive, especially those proposed by the EU. Such policies have the potential to constrict innovation and keep significant control over the GAI industries mostly within only the larger corporations who co-developed these policies and guidelines. In contrast, there are relatively less restrictive guidelines on the technology set by Singapore and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. While the core of the guidelines is similar to that of the G7 countries and the EU–I.e. Protecting human rights and interests, and proper representation of cultures and identities, the main differentiating factor is that Singapore’s guidelines are voluntary.

In an exclusive by Reuters, this decision for a voluntary set of guidelines by Singapore and ASEAN was stated to facilitate a “business-friendly approach” to GAI. This forward-thinking approach to business and revenue has long been Singapore’s strategy towards new technologies. First with robotics and computerisation, the approach is once again demonstrated by Singapore’s policy making around AI technologies. In their paper, Regulating Artificial Intelligence: Maximising Benefits and Minimising Harms, Soon and Tan documented the various endeavours that Singapore has been taking from as early as 2018 to ensure that the nation is ready for the disruption that AI technologies would come to bring. From various data policy guidelines and strategies to the AI Verify framework and toolkit which aims to encourage “transparency, explainability, repeatability, reproducibility, safety, security, robustness, fairness, data governance, accountability, human agency and oversight, and inclusive growth, societal and environmental well-being” in AI providers. And despite these frameworks once again leaving out GAI and the creative industries, the principles still apply as they are general policies that seek to protect its citizens.

That said, as mentioned above, these policies, as with those by the United States, are on a voluntary basis. As such, there are no disincentives for companies and other AI providers to work within the framework, especially if doing so would come at an additional cost to them. Additionally, in a press release by the Ministry of Home Affairs Singapore for the U.S.-Singapore Critical and Emerging Technology Dialogue: Joint Vision Statement, it is explicitly stated that by introducing voluntary guidelines, Singapore is looking towards promoting “inclusive and sustainable economic growth” that also ensures that “small- and medium-enterprises can benefit”, which contrasts with the EU’s stance on regulation.

Navigating the contemporary regulatory landscape for AI presents a significant challenge for governments. On one hand, governments in ASEAN express concerns that the EU's approach may restrict innovation due to its perceived aggressiveness. On the other hand, while Singapore's 'hands-free' regulatory approach may seem well-intentioned, the lack of enforcement raises questions about the nation's priorities beyond simply economic growth as a neoliberal society.

Creatives, Technology and Capitalism

Just as the emergence of the printing press had reduced the barriers of entry to knowledge by allowing the greater accessed to books and prints by the masses, the emergence and rising popularity of GAI have now also significantly reduced the barriers of entry to the creative industries. Where a creative professional had traditionally needed to learn fundamental skills such as grid systems and the basics of typography, an average non-creative is now able to begin creating their own books, illustrations, designs, and multimedia content like photographs, videos and animations, all from typing a few keywords into a text field.

However, while GAI might arguably be the catalyst for the next step in the evolution of the creative process, potentially even allowing many non-creative professionals to engage with the creative process, it does appear that at the time of writing, the technology seems to be used more as a tool for earning a quick profit instead. This is far from a technology-related problem, but rather, a problem that has stuck with the creative industries from its earliest conceptions.

Profit maximisation through the creative industries is not a novel idea. As advertising and branding design gained prominence in the last century, creative ideas and the artistry behind the craft skills have been noted to be increasingly limited by clients and stakeholders in favour of efficiency and formulaic designs. This phenomenon, labelled as consumer engineering in Ruben Pater’s book, Caps Lock: How Capitalism Took Hold of Graphic Design, and how to Escape it, utilises the theories of Sigmund Freud to tap on people’s subconscious desires in order to sell them products. As Victor Papanek expressed, designers are another commodity for businesses. Being delegated to the production of toys to ensure that the consumer maintains the cycle of “buying, collecting” and “discarding useless, expensive trash.”

In recent years, as consumers begin to weigh a company’s values against the products that they are selling, the companies have followed suit. Working together with insights garnered from societal feedback, contemporary brand strategies ensure that their messaging and brand values match the beliefs of the highest percentage of consumers. This in turn ensures that consumers will resonate with the stance that the brand has taken and will in turn, continue to drive revenue, regardless of whether the brand actually believes in its stance or not. As Kanai and Gill observed, this is not a new trend. Companies, run by those in power, have long utilised rebellion and cultural conflicts as agents for sales and marketing, redirecting the attention surrounding the real world issues back onto themselves.

What this implies for the creative industries is, in a chase for the next data-driven insight or controversy, the hands of creative professionals are tied by their clients and stakeholders. Where once design and creative work used to be led by creative professionals, it is now led by executives, strategists and data scientists who as Pater expressed, “spends all day thinking how to make people click on ads”. Some might argue that this is the nature of the creative industries, where the role is to simply be problem solvers for businesses to achieve their underlying goals of revenue generation. However, it does not invalidate the fact that the creative skillset has long become a commodity used by capitalism for the sole purpose of generating revenue.

This is a crucial point to understanding the motivations behind the recent rise of, and adoption of creative automation technologies. When bringing GAI and AI technologies back into this discussion, the rationale behind the push for the technologies is now clearer. To repeat the example from the above-mentioned Davenport and Miller investigation into local and international companies already utilising AI in their workflows. By doing so, companies would be more efficient and at least save costs, if not generating more revenue. While this is not necessarily a negative outcome, as to some extent it does align with Mill’s view on utilitarianism for the greater good where greater profits would in turn result in a economical growth. However, it also aligns with Marx’s and Papanek’s criticisms on capitalism, where despite an increased productivity and revenue, the workload and income of the working class is worse if not the same. Generative AI tools have been touted by those who sell them to augment rather than automate creative workers. But the example of Buzzfeed, and several others who have since replaced or “augmented” their workers with generative AI definitely does expose some of the flaws in this logic of thinking.

Research Objective

Through the reviewed literature as summarised above, it is evident that there exists significant existing research surrounding the topic of AI, GAI, and the ethical considerations in relation to AI technologies, the creative industries in relation to capitalism, and the evolution of the creative industry. However, there still exists several gaps within the existing literature, especially considering the novel and cutting edge nature of GAI technology at the time of writing in 2023. Two such gaps have been identified as follows.

First, much of the reviewed literature surrounds industries outside of the creative industries such as business management, engineering, and manual labour industries like construction, and work in the production line. While there has been emerging research in the discussion of the impacts of GAI within the creative industries, the amount of research at the time of writing remains sparse, largely discussing regulation and data ownership rather than its implications on the creative process.

Second, there is an overall lack of research regarding generative AI and its impact on the creative industries within the context of Singapore. As discussed in the literature review, the bulk of the discourse of GAI in discussions internationally and in Singapore’s context is often held in fields of education, data ownership, and policy making. These discussions predominantly focus on broader societal issues, thus leaving a gap for research that seeks to investigate the immediate impacts of GAI on the local creative industries.

As such, while governments and academics around the world rush to respond to the emergence and rise of the GAI, this research seeks to take a step back to fill in the highlighted gaps. Specifically, this research seeks to investigate on a qualitative level, how the local creative industries are perceiving and responding to the emergence and rise of GAI.

The research seeks to accomplish this through the investigation of the following research questions:

1. What are the driving factors for the push for automating and/or augmenting creative work in the markets?

2. To what extent would generative AI impact the nature of creative work in the commercial creative and design industries, and its processes?

3. How is the creative industry in Singapore currently perceiving this issue as a whole, and how do they feel about generative AI in relation to their creative processes and workflow?

The research will then use its qualitative findings to inform a discussion that speculates and predicts the impact of the emergence of GAI on the creative industries in Singapore.

Approaches & Methods

To achieve the objectives as described above, the following methodology is proposed. First, as demonstrated from the literature review, desk research through a deep survey of relevant literature has been conducted. This is to minimise the risk of repeated research and invalid contradictions. The review has also been accompanied by thoughts from various relevant thinkers such as Karl Marx, Walter Benjamin, Guy Julier, Victor Papanek, and John Stuart Mill.

Primary Methodology

The core of this research will be conducted through the primary research method. That is, a series of moderated one-on-one interviews with subject experts. These experts have been chosen for their respective expertise in GAI research, their hands-on experience with GAI in commercial creative work, and their knowledge of the creative industries within Singapore. To promote representative sampling, creatives who reside and work in Singapore were prioritised, ensuring that they came from a range of backgrounds in terms of gender, race, industry specialisation, and levels of expertise. For example, while all participants are seasoned professionals in the design industry, their responsibilities range from those who lead large multinational creative departments to those who run boutique agencies on a smaller scale. The specialisations of these participants also vary across different creative fields like user experience and digital product design, to video production. Voices from academia have also been approached for an additional point of view. This strategy is designed to facilitate a broad spectrum of perspectives, thereby reducing the sampling biases that are often a challenge in qualitative research.

Interviews are utilised as the primary research method here as it aids to create a foundational qualitative understanding of some local creatives’ impressions of these technologies. As this series of interviews sought to explore the unknown, a semi-structured discussion guide had been designed to facilitate open-ended discussions of the topic. This discussion guide covers three major themes in alignment with the research questions for a total of six primary questions. Each primary question is further accompanied by a few potential follow-up questions based on how the participant is expected to respond based on the reviewed literature. The discussion guide is adaptive, and questions were added and omitted during the interviews themselves as necessary to sustain the natural flow of the conversation.

At the point of conclusion for this study, of the 14 subject experts approached, 8 experts had expressed interest in participating, of which 6 have been interviewed. The interview was reworked into a questionnaire form for participant 6 due to scheduling complications. The profiles of the participants are as follows:

1. Participant 1 – Part-time design educator and Co-Founder of a boutique video production agency

2. Participant 2 – Co-founder & Creative Director of a boutique digital transformation agency

3. Participant 3 – Associate Professor at a local autonomous Singapore university

4. Participant 4 – Active AI keynote speaker and Co-founder of a boutique marketing agency

5. Participant 5 – Regional head of a global creative consultancy

6. Participant 6 – Part-time design educator and Co-Founder of a boutique design agency

Prior to being interviewed, participants were also requested to review and sign the attached informed consent forms. This was to ensure that participants were aware of the privacy and data protection policies of Lasalle as an institution, and to also ensure that they understood the nature of the study that they were to take part in. The interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim to the best of the researcher’s abilities. Each transcript was then cleaned up to remove non-verbal expressions, with the rest of the transcript remaining intact. After the interviews had concluded, the transcriptions were broken down and coded with categories with reference to the framework for analysing qualitative interview data as written by Philip Burnard in 1991. The categories were induced based on the contents of each notable quote by each participant and were filtered and recoded twice to minimise discrepancies. The final code count ended with 3 primary codes, with each representing the theme of the research, accompanied by 21 sub-codes.

Discussion

Interview Results

The goal of this series of interviews is to investigate how creative professionals in Singapore perceive the GAI discourse. Specifically, the study sought to discover what the participants felt were the primary contributing factors to the rise of GAI since mid-2022, how the participants felt that GAI might come to impact the nature of the creative industry, and uncover any additional perceptions and impressions that these creative professionals might have regarding GAI. As previously mentioned, 3 primary categories of findings were discovered during thematic analysis. The categories, which seek to answer each research question, are as follows: the rationale for increased GAI adoption, the perceptions of GAI by local creatives, and the potential impact of GAI on the creative industries.

Rationale for Increased Gen AI adoption

As previously mentioned, the idea of using technology to augment one’s workflow is not a new concept, with new technologies periodically finding themselves acting as the catalyst for the evolution of the creative industries. However, the current virality surrounding GAI technologies and the industrial push to integrate these technologies into the creative workflow is a significant factor worth investigating. By understanding this sudden industrial push for GAI in the creative industries, it would contribute to making an informed prediction of the potential impacts of GAI on the creative industries and the creative profession.

One might be quick to assume that the main rationale for the sudden increase in GAI adoption and media coverage is due to the technological progress of the diffusion models and the emergence of GAI technologies mentioned above. However, it was found that only a few of the participants (n = 2) attributed the rise of GAI to said technological advancements. Instead, there were two other reasons that participants felt were more impactful contributors to the hype of GAI.

“These are the same people who brought the hype marketing to Crypto. So it is no coincidence that A.I. has the same hype as Crypto did two years ago, because it is the exact same experts who are running the show.”

- Participant 1

First, some participants (n = 4) believed that a considerable factor for the industrial push of GAI was due to a financial obligation held by businesses, organisations and professionals to optimise revenue generation. As evidenced in the examples outlined in the reviewed literature, GAI technologies has made the creative process considerably more efficient and accessible. Users of the technology can now produce creative works for profit without ever having gone through formal creative-related education. Creative freelancers around the world are now able to take on more projects and complete them in a shorter duration. And in cases similar to Buzzfeed, companies are now able to start automating creative work to some extent, that up until the emergence of GAI technology, was seen as the last bastion of humanity that AI could not replace.

Additionally, the hype behind GAI appeared shortly after the the post-pandemic era in the middle of 2022, at about the same time that large players in the Cryptocurrency, NFT and Web3 industries were falling. As participant 1 explained, “from Tesla, many of these people migrated to the next big thing which was Crypto and Web3, followed by NFTs.”, and “A.I. was on the coattails of NFTs”. This was also noted by participant 3 in a similar observation, “In a much narrower view, blockchain and bitcoin and all the related Web3 services have been disappointing for a lot of investors because of their volatility, and because they don’t understand it. And I think that’s what brought this service (AI) that is dead simple to grasp.” Suggesting that there was a significant financial incentive for the markets to ensure that there was a new technological innovation to hype up and ride on.

However, the financial sub-factor alone would likely be insufficient without the second sub-factor–that is the accessibility of the GAI tools. Most participants (n = 5) agreed that accessibility was the most significant contributor to the hype behind GAI. All participants (n = 6) described GAI as a tool or service that “had no upfront capital on the user’s side”, “everyone would just type some words and get an image”, and “the way it presents itself, there’s no learning curve. There’s nothing for me to learn, there’s no barrier of entry for me. It was free, so all I needed was to set up and account and boom, I could use it.” As previously noted, the invention of GAI technologies like GANs and diffusion models have been around for nearly a decade, but it is only due to these sub-factors that the technology has finally hit mainstream media coverage and discussion, and thus an overall industrial and market push for GAI integration into the creative process.

The findings from the interviews corroborates well with the points made by the literature reviewed. As noted by Victor Papanek and other creative thought leaders, the creative industry has already previously been commodified. The role of many creative professionals had long been relegated to simply following the requirements of the brief and market data that accompanies it, usually under the premise of “solving problems” for their business stakeholders. While on one hand, the commodification of the creative industry has been profitable for the businesses that utilise their services, which as previously mentioned, can be seen as an “overall good” under Mill’s Utilitarianism. However it does undermine the value that the creative industries bring with its capabilities. A common theme observed throughout all six interviews was an unconscious acceptance of the commodification of the creative industry by the participants. All participants (n = 6) effectively expressed that the industry, and by extension, their work, was simply a means to an end. For the people who require their services to profit, which in turn, contributes to their financial gain. While this is not inherently negative, however, as previously mentioned, the commodification of the creative industry has been a concern from its earliest conceptions. And with the emergence of GAI, as well as the push for its integration into the creative industry, this phenomenon is likely to be further amplified. As one participant expressed “It just needs to achieve results, and AI can actually target and create more content to the point that it actually meets the needs–you can set targets, and the algorithm is actually better than humans at predicting what people are going to buy.” Which does continue to beg the question, where is the creative’s place in the creative industry today?

Perceptions of Gen AI by Local Creatives

“As a creative director, there are things that I can put into the prompt based on my years of experience. Nobody can replace that. Someone new can’t come in and say “Oh I can replace a photographer, I will write my prompts”. Because you don’t have those years of experience that you need to get that perfect image or that great piece of art. It’s experience + AI. That’s my experience.”

- Participant 4

This category explores the perceptions and impressions that the local creatives interviewed hold towards GAI. First and foremost, all participants (n = 6) view the capabilities of GAI in a favourable light in some capacity. While the idea of typing a prompt into a chat bot and receiving a generated image in return was an initially novel experience, that quickly wore off for most participants. Instead, where participants found value in GAI were in use cases surrounding ideation and streamlining one’s workflow. As one participant expressed, “I would say it definitely helps a lot in augmenting the creative process but not at the stage where it can totally replace human input.” This is a sentiment shared by all other participants who believe that GAI technologies such as the previously mentioned MidJourney, DALL-E, Stable Diffusion and ChatGPT are simply the next iteration of tools for the creative professionals. Rather than complete automation, the view of the participants on GAI surprisingly align with that of global organisations like IBM and the World Economic Forum. The view being that current GAI tools are not just simple solutions that can replace all aspects of creative work, rather, still requiring significant experimentation and learning to be able to learn and utilise the tool to its full potential. As some participants described their experience of working with AI, “it doesn’t prove to be always useful, but it may start a conversation and bring up interesting points”, and “at the end of the day, it is another tool which you cannot blindly follow.”

Despite not finding full value in GAI now, participants acknowledge that GAI is a technology that will come to advance the creative industries. As one participant explained, “the notion of a paradigm change is not new at all to us. The same way as how typewriters replaced handwriting or how cars replaced horses. All of those clichés all apply to generative AI”. Participants appeared to view GAI as a new medium or canvas of sorts, a new craft that one can get good at eventually. However, current commercial uses of GAI in the industry have been noted by some participants to only consist of rudimentary explorations, done for the sake of simply exclaiming that one is able to use GAI in their workflow. While the participants did not give specific examples, their observations do corroborate with the literature reviewed. For example, prominent digital product and marketing company R/GA had attempted to integrate GAI into their solution for the Singapore Association of Mental Health in the third quarter of 2023. With support by the art styles requested by the patients, the team at R/GA was able to use GAI to generate and curate works of art that visually represented the feelings of SAMH’s patients, presenting a different outlet for its audience to empathise with people with such disorders. However, beyond the visual material generated, there was more left to be desired from such an application of GAI. As participant 5 explained when asked about the industry’s current use of GAI, “It could be so many things, and not everyone can do it at that scale. There’s that one off where you do a campaign and use ChatGPT, MidJourney, and a couple of APIs for two weeks, and that’s fine. More people could do that. But to do it at scale is very different.” Overall, in terms of both local and international commercial work, GAI does appear to still be considered an experimental technology and thus has yet to be fully integrated into commercial creative workflows beyond the individual level. That said, as mentioned above, participants do believe that this will come to change over time.

Potential Impacts of Gen AI

As evidenced in the literature reviewed, the impacts of GAI has already begun to be felt globally. Governments are racing to establish guardrails and regulations. Many creative professionals and organisations globally are progressively integrating GAI technology into their workflow or product and service offerings in some way or another. Additionally, as demonstrated in the section above, the participants interviewed also shared similar observations and experiences in relation to the industry’s exponential adoption of GAI tools. However, as the capabilities of GAI technology continues to be iterated on, one might question how this would come to impact the creative industries. That said, it is important to note that this is a speculative discussion based on current events, the current GAI technology available for use, and the experiences and impressions of GAI by the participants. This is by no means a prediction of the future impacts of GAI.

One primary concern behind the research objectives was that due to the highly limited ways that current GAI tools are being trained, that beyond representation and accuracy issues, there would be a saturation point in the future where all generations start to look alike. This is because of this researcher’s understanding that GAI tools are only capable of generations based of their training data. While the generations can be considered new creations, should there be minimal or no updates to the training, and assuming that the same models are the ones being used in the future, there would eventually be a point where all design looks homogeneous. However, as the interviews concluded, there was a realisation that this concern was unwarranted as it was heavily based on an assumption that GAI technology would stay in its current state for the foreseeable future. The probability of that being so was highly unlikely. As this participant explained, “Right now it’s generic because AI is still learning and generalising. But the moment you pull the walls on that, and allow the AI to learn about the user, I think every output is gonna be unique”. In fact, due to the ever learning nature of GAI technology, the opposite is more likely to happen. To paraphrase one participant’s comment, rather than a homogenous landscape of generated material, it would be more likely that said landscape be heterogeneous. However, what the industry does with this hypothetical GAI ability to produce highly diverse is another point for discussion.

From the interviews, it was found that all participants (n = 6) felt the disruption to the creative industry will arrive as a cumulation of several factors. First, current users of existing GAI technologies are already able to produce illustrations, books, photos, and long form written content. Hence, it would not be far fetched to imagine that business would be using these as case studies to optimise their creative processes. As this participant speculated, “the business model of the future will be that we will sell very good people. Maybe less people, so instead of a team of 10, we may only need 4 amazing people who use AI, with bigger abilities”. Elaborating on their speculation, “we tend to sell people’s time. We sell, let’s say 4 hours of an art director. So we need to start thinking of what’s the new model. So we may sell individuals with new abilities without selling their time.” While not all participants described the same speculative scenario, the concurrent sentiment shared by all participants was that as GAI improved its ability to remove laborious tasks from each creative’s process, there would be an exponential increase in the amount of resources freed up for businesses, hence requiring lesser employed creatives. When asked about how a creative professional could remain relevant in such a scenario, all participants shared suggestions of being open to new technologies early and learning new skills such as computational skills to fit within the new “hybrid” professionals of the “future creative team”. One has to be equipped with “creativity, “good taste, but at the same time have a modern tool kit”. However, as with how Marx noted in his chapter on machines in Capital, upskilling oneself does little for the fact that countless jobs would still disappear in the industry that is being disrupted. There remains the possibility that creative professionals who are ultimately displaced out of the industry could reskill themselves into other industries or even the same industry. And in the local context of Singapore as noted by Lee, there has been several governmental efforts that ensures to keep its citizens employed such as the SkillsFuture movement. However, without further systematic analysis on how emerging technologies like GAI would come to impact the future of work and the wider economy beyond 2030, it is difficult to argue that the emergence of GAI would be a nett positive for creative professionals.

That said, while creative professionals look towards remaining relevant as GAI increasingly optimises their processes, there is little doubt that the disruption of the creative industries by GAI will be a nett positive for the businesses and corporations in said industry. As explained by this participant, “AI levels the playing field and now size doesn’t matter. What an agency like Oglivy could do with 150 creatives, an agency that’s smaller can–that’s one of the key points with generative AI. There are so many things that you can’t do without a lot of hands and people, that now you can do with AI”. Additionally, it is not only the smaller creative businesses that benefit, but also the larger creative corporations or projects that will now able to produce significantly more while using less financial resources.

In relation to society, the impacts of GAI can arguably be speculated to have a nett positive impact. Due to its ability to democratise the creative skillset, many crafts that once required significant formal education and training to pursue, are now accessible to the mass population should they choose to adopt these tools. As mentioned above, all participants (n = 6) do not believe that the current capabilities of GAI is sufficient for commercial use, especially in its production and execution capabilities. However, as evidenced in the literature review, this did not stop the surge of content being produced by non-creative professionals. This phenomenon is likely to be amplified as the technology improves. Additionally, as speculated by this participant, “You will have people who appreciate creativity, but are not creative themselves. So these people, if they can control these systems, they can become the new creatives as well”, implying that many non-creative professionals might also be able to enter creative positions within their organisations as they gain competencies over the GAI tools.

However, with the democratisation of the creative skillset, comes another cause for concern. That is, the potential for a diminished appreciation of the creative craft. This phenomenon is already observable today. As noted by several participants (n = 4), many businesses currently take a templated approach to creative briefs, relying on trends and techniques that have found success repeatedly in the past. And in doing so, slowly whittles away at the aspects of production requiring innovation and creativity. When asked for the rationale behind this, one participant explained, “before there was Facebook and Social Media, you didn’t have the crunch of time. You didn’t have to rush through–right now, everything is moving much faster. That speed is something that humans really can’t complete on their own, without the help of AI. If someone else, another brand or another creative is using AI, and doing it a lot faster, you won’t be able to compete“. This corroborates with the literature reviewed as well. The fact that due to the capitalist nature of the creative industry, there is a need to efficiently produce more so that the businesses can generate more profit, as is their obligation to their shareholders and other stakeholders, including their employees. However, what this could potentially result in, is that due to the waves of content that focuses less on the craft, that the average consumer’s taste in the quality of production will be further reduced, which as one participant speculates, “the dangers I see there more is that we’re not changing fast enough in that direction that the market force will default to the median, and start to dissipate the advantage of the unique and creative content created, and it won’t be as valuable, and you won’t find a customer that is willing to pay for it. Not that there’s anything wrong with it, but because the mass consumer prefers to have a mediocre output.” This was similarly noted by another participant who observed that a number of clients who work with their peers have begun looking toward GAI or freelance services for services such as logo design, which traditionally could be costly for businesses. However, that participant also emphasised that there will always be a place for creatives to push the boundaries of creativity as there will always be businesses that will require their services for more catered solutions. This sentiment was also similarly expressed by the previous participant who speculated, “the same way you may have artisans for furniture or coffee. Maybe using photoshop the way it is today, in the future, may be artisanal.” Hence, as mentioned previously, while the capabilities of GAI tools in the future will continue to be heterogeneous to some extent, there is a real possibility that said capability will instead be used for creating creative work that eventually lowers society’s expected standards for the quality of the craft.

Two other impacts were also briefly discussed during the interviews but were not the main focus of this study. The additional impacts discussed were concerns around data ownership and correct representation in training data. Throughout the interviews, there was a common agreement that plagiarism and stealing of content are not new phenomena. They are ultimately a societal problem that is being amplified and reflected back to society through GAI. As briefly mentioned in the literature reviewed, many GAI tools and the datasets used to train them have been indiscriminately scrapping data from all domains to which the GAI companies had access to. As of writing, while there is little legal precedence on the legality of such actions, there has been significant outrage from some across the creative industries claiming intellectual property violations. When asked about the situation, all participants (n = 6) do agree that there is plagiarism and the theft of content to some extent. However, interestingly, none of the participants brought up the idea of financially compensating the creatives or original owners of the data that was “stolen” to build the tools. Nor was there any discussion regarding the ability for one to opt-out of the tools using their data. Rather, most participants instead suggested ways of revamping GAI tools such that the data used could at least be tagged and be attributed back to the original creators, although the details of which were not discussed. That said, it can be speculated that should little action be taken against the GAI companies, there may be a significant shift in society’s understanding of intellectual properties, to which also has significant implications for the creative industries.

With regards to proper representation, some participants (n = 3) agreed that current GAI tools were highly misrepresentative of many cultures and communities. As this participant explained, “It’s conflicting with that because we are already saying that no we should not perpetuate certain messaging regarding gender, race, etc. But based on the A.I.’s way of working right now, it’s going in the opposite direction. Because clearly, we’re not going to be able to feed it enough data on the underrepresented.” This is further supported by the reviewed literature where generations of people, be it visual or text-based, were highly undiversified. Many of the generations were also observed to reinforce stereotypes. After all, as mentioned previously, GAI is simply a product of its training data. This characteristic of GAI has several potential implications for society moving forward as adoption of GAI increases. One alarming consequence being a lowered tolerance of other cultures and communities, which as one participant mentioned, is already being exacerbated by echo chambers and sources misinformation commonly found across social media and the internet. To combat this, the participants who expressed this concern for misrepresentation issues in GAI suggested similar solutions of building or revamping datasets that include significant amounts of data that properly represented cultures and communities that were previously be affected by the biases. As this participant explained, “Our biggest defence against that would be to support diversification by helping A.I. companies around the world to succeed not just in the Western markets”, and “these tools might not look as nice or polished but ultimately it helps us to democratise the space. So whatever we can do, we help them out and help the ecosystem as a whole.” This is further supported by Luccioni et al. in their study on analysing societal representations in Diffusion models, where they observed that tackling such misrepresentation in a pre-existing model is highly likely to instead amplify the biases. Hence this suggestion by the participants may be an alternative worth considering by GAI companies that wish to combat misrepresentation.

Notes for Further Research

Limitations

First and foremost, as one participant expressed “if you’re drawing a conclusion from early outputs of a technology that is dynamically evolving, and predicated on non-linear, dynamic training sets, and draw a linear conclusion from it, that might lead you to incorrect conclusions”. This is a point that this researcher wholly agrees with. In the grand scheme of time, GAI as a technology, while significant, has not existed for long. Hence, a paper such as this one that tries to evaluate and speculate the potential impacts might be considered rather premature. Additionally, due to the fast changing nature of a cutting edge technology like GAI, the study only covers events and literature written up to November 2023. Hence some of the points and concerns that were brought up during the discussion section of this paper may already have been resolved.

Lastly, as a qualitative study, this study is highly unrepresentative of the thoughts and impressions of the population of the creative industries, both locally and internationally. Firstly, participants recruited consisted of solely industry veterans with considerable experience, hence there was no representation of other demographics of the creative industry such as junior or mid-level creative professionals. Secondly, while effort has already been made to diversify the sample interviewed, due to the small sample size, the representativeness of the current findings cannot be accounted for either.

Potential for Further Research

Despite the limitations of this study, the findings do provide a foundational understanding for further research which was the above mentioned objective of the research. Potential directions for further research include measuring the representativeness and validity of the findings, or conducting a similar qualitative study on other demographics within the creative industries which may provide valuable insights on how different demographics of creative professionals might perceive GAI as a whole.

Conclusion

To conclude, it would appear from the interviews that there is significant corroboration of the impressions of veteran creative professionals towards GAI to the literature reviewed. Participants mostly agree that the virality behind GAI is due to the accessibility and ease of use of GAI tools, which are being supported by the high potential of financial benefits that businesses and investors may gain. That said, none currently find great use for GAI tools for the execution and production aspect of their creative work.

Additionally, while the participants do see business value and the future potential for the creative process to evolve through the continuing development of GAI tools, all have raised several concerns regarding industry disruption and potential for significant levels of creative unemployment. Concerns also include the potential for the appreciation of creativity, creative professionals and the creative skillsets to be increasingly less valued by businesses and consumers, a phenomenon that has been long occurring and commented on by age-old industry thinkers like the previously mentioned Victor Papanek.

Overall, despite this study’s considerably generic line of inquiry, due to its setting of Singapore, it does lay a considerable foundation for those who might seek to learn more about how Singaporean creative professionals are perceiving the current hype around GAI. That said, as a qualitative study, it is uncertain as to exactly how representative the findings of the study are. Hence further research, especially that of longitudinal scale, is strongly recommended to further evaluate the representativeness and validity of this study.

Author

This study was driven by Tan Wei Ren, Ryan as part of their graduation coursework at Lasalle College of the Arts (Now UAS-Lasalle). The study was supported by Andreas Schlegel as academic supervisor.

Other Research

This project was backed by three driving forms of research into generative AI. Literature reviews of current gen AI research; Qualitative interviews with local creative industry veterans; And technical experimentation with various generative AIs.

Repository

A collection of my most impactful references and resources used for this project.

View REPOSITORY

Catalogue of Making

A visual collection of all technical experimentation conducted for this project.

View Catalogue